Reversals

In 1614, Sir Thomas Roe, London’s first emissary to India, visited the Mughal emperor Jahangir. But turns out, Jahangir was not very interested in the meeting. At the time, the Mughals were rulers of the greatest and richest empire in the world, and England was deemed not worthy of their attention at all.

And no wonder: The Mughal empire spanned most of present day India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Afghanistan, about 1.5 million square miles, more than 15 times that of England. The empire covered a fifth of humanity, about 150 million people. Its standing army alone of 4 million was bigger than the population of England.

But, of course, by 1858, India was a colony of the British empire.

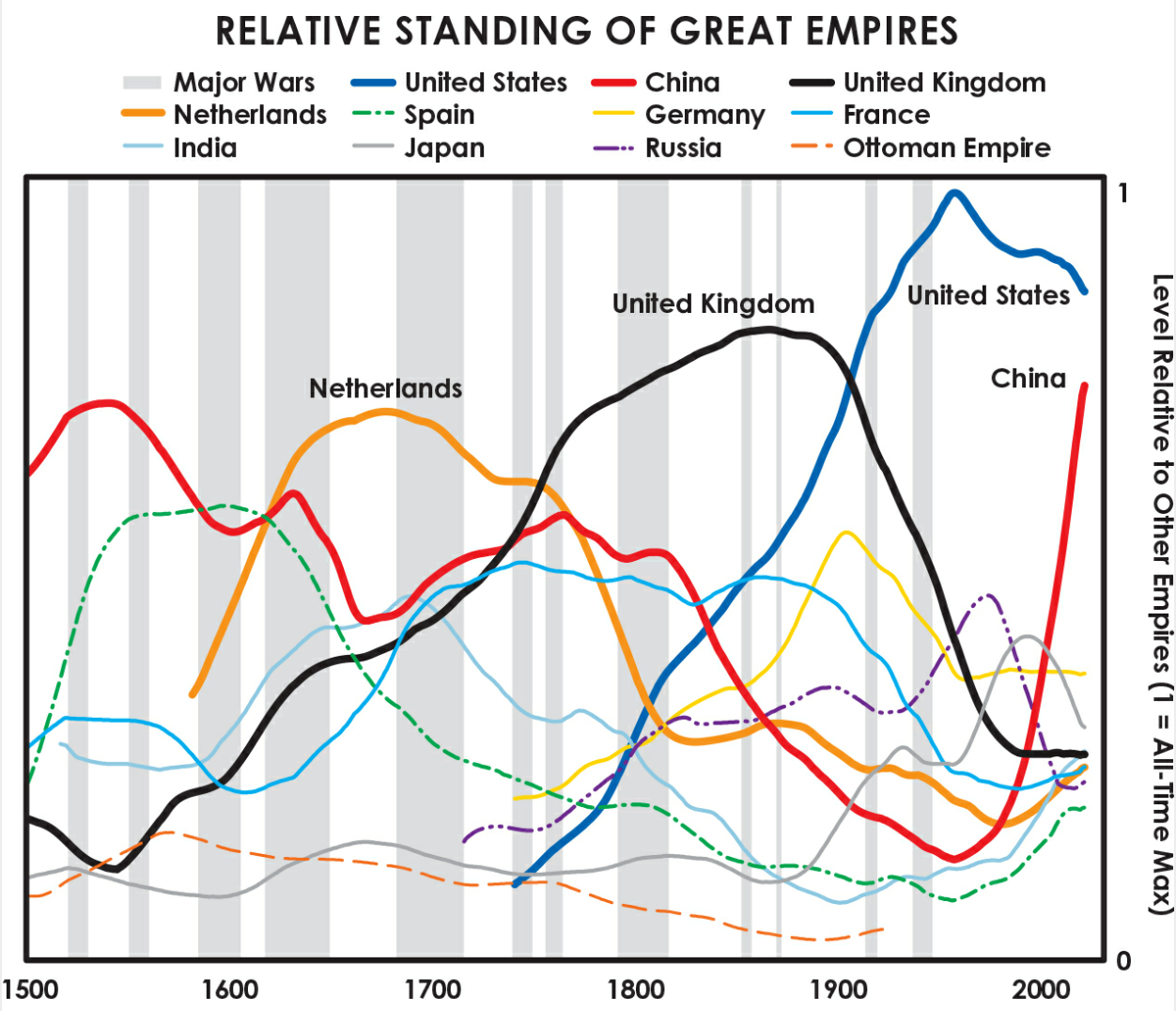

And that was the peak of the British empire. According to Ray Dalio, the empire began to decline shortly thereafter:

That decline is really only clear in hindsight, of course. For the first half the twentieth century, the British empire certainly felt mighty to many observers. Consider the observations of Singapore’s founder and first prime minister, Lee Kuan Yew, as he reflected back to the 1930s, when Singapore was a British colony:

…By the time I went to school in 1930, I was aware that the Englishman was the big boss, and those who were white like him were also bosses – some big, others not so big, but all bosses. They had superior lifestyles and lived separately from the Asiatics, as we were then called. They ate superior food with plenty of meat and milk products. Every three years they went “home” to England for three to six months at a time to recuperate from the enervating climate of equatorial Singapore. Their children also went “home” to be educated, not to Singapore schools. They, too, led superior lives. At Raffles College, the teaching staff were all white. Two of the best local graduates with class one diplomas for physics and chemistry were appointed “demonstrators”, but at much lower salaries, and they had to get London external BSc degrees to gain this status. One of the best arts graduates of his time with a class one diploma for economics, Goh Keng Swee (later to be deputy prime minister), was a tutor, not a lecturer.

There was no question of any resentment. The superior status of the British in government and society was simply a fact of life. After all, they were the greatest people in the world. They had the biggest empire that history had ever known, stretching over all time zones, across all four oceans and five continents.

But soon Lee Kuan Yew would realize that his perception of the British empire and the reality were quite different. On February 15, 1942, British forces surrendered Singapore to Japan. It was a shocking and humiliating defeat. The Japanese captured the island, along with 80,000 British, Australian, and Indian troops, with relative ease. Winston Churchill called it “the worst disaster and largest capitulation in British history."

The following four years of occupation were a turning point for Lee Kuan Yew. He called the experience the turning point of his life, his primary education. After Japan’s surrender following the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the British returned. But things were not the same. Lee Kuan Yew attended Cambridge and returned to Singapore with a firm belief that Singapore’s future did not include the British.

On August 9, 1965, Singapore gained independence, with Lee Kuan Yew as Prime Minister. It was actually an unexpected and unwelcome event because independence was not Lee Kuan Yew’s goal. In fact, he had been negotiating the merger of Singapore with the Federation of Malaya. The agreement fell apart at an advanced stage when it became clear that there would be significant issues incorporating Singapore’s majority Chinese majority population into the Malay dominant federation.

Independence should have been a joyful and optimistic event, but the country’s birth was more like that of a prematurely born baby with little chance of survival. Singapore was a tiny island with no fresh water, no independent military, limited natural resources, and a largely uneducated, impoverished population, not to mention simmering tensions between its Chinese and Malay populations.

But what followed over the course of one generation, largely due to Lee Kuan Yew’s leadership, perseverance, and sheer force of will, is one of the greatest success stories in history.

Singapore’s GDP per capita in 1968 was $500; in 2022, it was $83,000, the sixth highest in the world (just higher than that of the US and meaningfully higher than that of the UK, whom it surpassed long ago). The country is a role model for competent government, fiscal responsibility, and a stable, business-friendly political environment with little corruption. It consistently runs a fiscal surplus, despite investing heavily in its population, particularly on education.

Britain’s trajectory since 1968 has been quite different, best summarized in a recent article with the pretty direct title “Britain is Dead”:

[The United Kingdom’s] overall trajectory becomes obvious when you look at outcomes in productivity, investment, capacity, research and development, growth, quality of life, GDP per capita, wealth distribution, and real wage growth measured by unit labor cost. All are either falling or stagnant. Reporting from the Financial Times has claimed that at current levels, the UK will be poorer than Poland in a decade, and will have a lower median real income than Slovenia by 2024. Many provincial areas already have lower GDPs than Eastern Europe.

Huw Pill, Chief Economist of the Bank of England, recently said that British businesses and households need to “accept that they’re worse off” due to recent inflationary pressures.

The grand sweep of events is both humbling and inspiring: In the seventeenth century, the Mughal empire reigned supreme, and England was a backwater. By the nineteenth century, the Mughals faded into history, and the British Empire ruled the world. In the early twentieth century, a young boy perceived his white masters’ place at the top of the world as so firm and complete that “there was no question of any resentment…it was simply a fact of life.” After all, “they were the greatest people in the world.” The awe they inspired was well-deserved: “…they had the biggest empire that history had ever known, stretching over all time zones, across all four oceans and five continents.” But within one generation, that young man raised his country to incredible heights, and the British Empire crumbled.

Obviously, there’s much more nuance to all of these stories, but the main takeaway for me from these reversals is one of humility (success is hard to maintain) and perseverance (humble beginnings can lead to remarkable success).

Sources:

"Courting India — the unpromising sources of British power” by William Dalrymple in The Financial Times, March 16, 2023 (link)

The Changing World Order by Ray Dalio

The Singapore Story by Lee Kuan Yew

“Britain is Dead” by Samuel McIlhagga in Palladium Magazine, April 27, 2023 (link)