The (mis)Behavior of Markets

One goal of this blog is to find new ideas that challenge orthodoxy. It’s easy to look back at discarded ideas like geocentrism and laugh at how obviously they were wrong. But it certainly wasn’t obvious at the time. And it doesn’t take a dramatic leap of imagination to realize that clearly there are many ideas we hold today and believe accurately reflect reality that will actually be proven to be wrong later.

Modern finance is fertile ground for this dynamic. In fact, many highly paid and respected practitioners of modern finance continue have held on to ideas long past the point when their flaws were obvious.

To highlight this point, Mandelbrot tells about a joke Warren Buffett once made—that he’d like to fund university chairs in the Efficient Market Hypothesis in order to train more misguided investors and ultimately increase his advantage in the marketplace.

I was drawn to Benoit Mandelbrot’s book The (mis)Behavior of Markets because Mandelbrot was known throughout his career to challenge core assumptions in modern finance.

I was also drawn to the book because fractals have long been interesting to me. As a child with a certain nerdy, bookish disposition, I discovered James Gleick’s book Chaos at a young age and learned about fractals, patterns that are the same at various levels.

The idea of repeating patterns at different levels of scale stuck with me, and it was one mental model that led me to believe Bitcoin is on a path to be even more valuable and impactful than it is today.

The core message of Mandelbrot’s book is as follows:

Just as there are three states of matter—solid, liquid, and gas—imagine three states of randomness: mild, medium, and wild.

Conventional financial theory assumes that randomness only occurs in the “mild” state. From the perspective of this theory, real prices “misbehave” often.

A more accurate view of randomness in financial theory can be described with “fractally wild randomness”—a model that describes diverse natural phenomena, from fluid dynamics to electrical “flicker” noise.

In short: markets are riskier than you think.

The book is at its best with pictures, which isn’t surprising, considering that’s how Mandelbrot thinks.

For example, the core of finance rests on what is called the Bechalier Brownian motion model, which assumes that each day’s price change is independent of the last and follows the mildly random pattern predicted by the bell curve.

However, a simple analysis of the Dow Jones Industrial Average between 1916 and 2002 shows that this isn’t true.

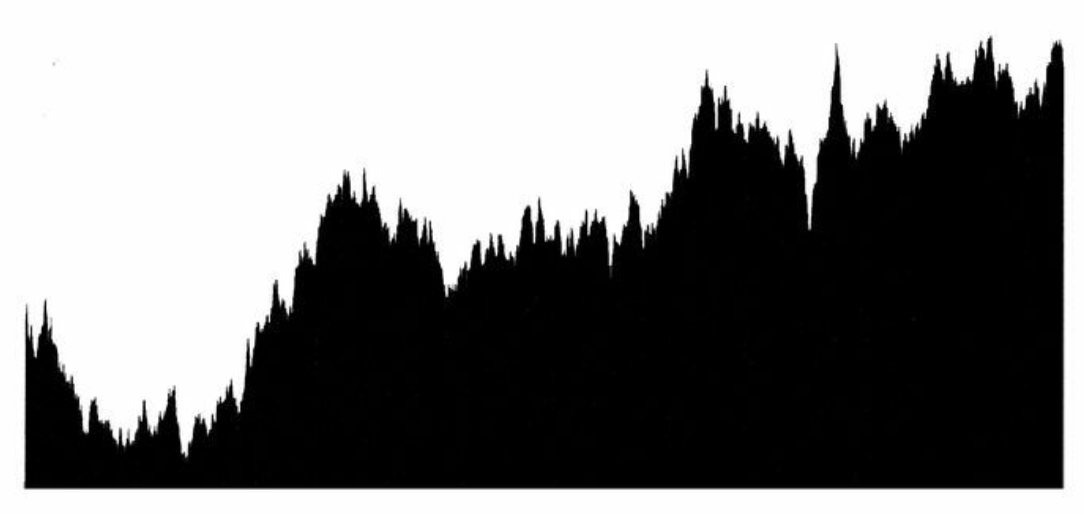

Here’s the DJIA in its familiar form between 1916 and 2002:

Here’s that same chart in logarithmic scale:

Here’s the daily change in the DJIA in log scale:

You can immediately see that, one, there are some very extreme events and, two, they tend to concentrate together, contradicting both assumptions of the conventional model.

To further illustrate the point, Mandelbrot goes a step further: he manufactures a chart using the assumptions in the conventional model.

Here’s the manufactured chart:

It looks somewhat realistic. But when you look at the daily change, you immediately realize it doesn’t reflect reality.

Here’s what that manufactured chart looks like in daily changes in standard deviations:

Here’s what the DJIA actually looks like in daily changes in standard deviations:

Mandelbrot points out that the conventional model, by definition, sees changes that are “small” (less than one standard deviation) 68 percent of the time; 95 percent of the time, it will see changes less than two standard deviations (2σ); and 98 percent of the time, it will changes that are less than three standard deviations (3σ).

In reality, however, the DJIA with some regularity sees spikes that are 10σ. And the 1987 crash was a 22σ event, the odds of which according to the conventional model are one in 10 to the 50th power. Mandelbrot kindly places that number into perspective:

“It is a number outside the scale of nature. You could span the powers of ten from the smallest subatomic particle to the breadth of the measurable universe—and still never meet such a number.”

In other words, it’s impossible according to the assumptions in our standard models of finance. And yet there it is.

It’s maddening to think that despite reality repeatedly showing the model isn’t true, practitioners cling to it.

The rest of the book is worthwhile, too, and worth a read. It’s worth noting that Mandelbrot admits the alternative theories need a lot more work. His goal is simply to encourage others to pursue the alternatives so that we may emerge with better models.

What I took away from the book are the following:

Downside risk. Markets are riskier than we believe, and we should act accordingly. (Insurance in the form of options protecting against extreme events may be a good value if it’s systematically underpriced.)

Upside opportunity. I believe the inverse is true, too—that we aren’t thinking properly about the upside benefit of positive extreme events, and I believe this is at the core of investing in technology and innovation.